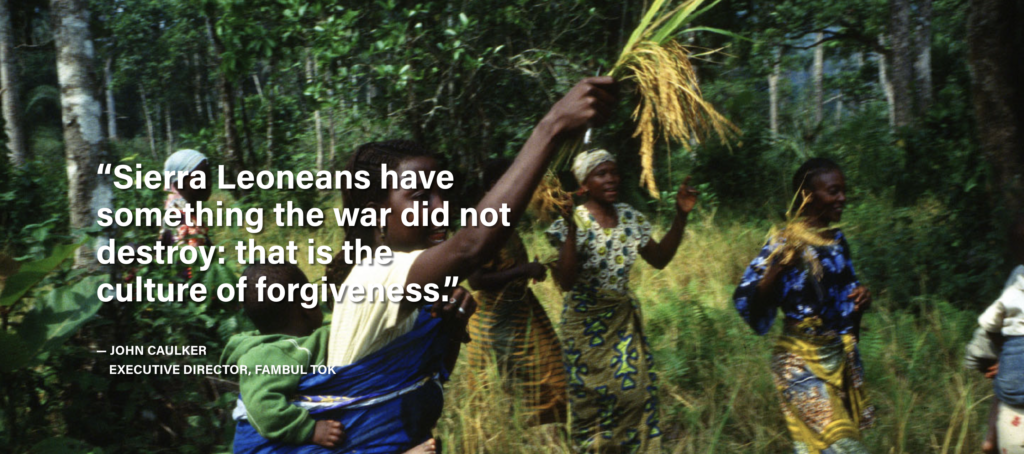

Fambul Tok: A Case Study of Reintegration, Reconciliation, and Cultural Practices in Sierra Leone

How rituals, rites and ceremonies can help with social healing, reintegration and rehabilitation after violence.

Authored by: John Caulker & Laura Webber (with foreword from Jesse Eaves)

Foreword

For the past two years, the Governance Futures Network has held a space called the Ritual Studio. This collection of individuals from around the world meets every month to explore how to meaningfully embed rituals and repetitive practices into governance processes to create cultures of care that can help us tackle complex problems in a more sustainable, inclusive, and holistic way.

We seek to create a space for caring, learning, and experimentation to explore how ritual can deepen relationships and help enable cultures of care to re-emerge as a central building block of relationships, agreements, and governance. We seek to shine a light on hidden bright spots and provide guidance, not solutions, by inviting wisdom from around the world and share it internally and externally.

This group is about showing that the future we imagine is already happening and being lived out by pockets of groups around the world. We call these existing practices “proofs of possibility”.

With that in mind, in February, we were joined by John Caulker and Laura Webber. John is the founder and executive director of Fambul Tok, a Sierra Leonean organization that led a nationwide movement for community reconciliation following the civil war that ended in the early 2000s. Laura Webber engages in research and practice at the nexus of trauma transformation, embodiment, social neuroscience, and social change. She centers a healing-based approach with an intersectional lens in her work toward conflict transformation from the individual to the collective.

Together, they joined Ritual Studio to discuss the origins of Fambul Tok, the role of rituals and practices in long term relational repair, and how “old practices” can be made new and germane again to feed the needs we have for deeper relationships with ourselves, our ancestors, and the earth. This linked directly to the purpose of the Governance Futures Network, which seeks to move away from top-down, control-oriented, and indirect forms of governance that were built for a pre-digital age and explore what sorts of agreements and practices can help us be together, care together, weave together, work together, and decide together as we take on the challenges of our times with a mix of old and new wisdom.

Some of the main lessons from the session were:

- Healing, accountability and reconciliation come from the collective; ritual can be used to create the sacred spaces that facilitates these processes.

- Escaping the western bias and that communities have the answers to their problems. As John said repeatedly “the answers are right there in the community”. When communities are put in the lead and connected through rituals and practices, they create an arc between their ancestors and future generations.

- The conversation surfaced the work of adaptation and evolution and honoring what is old and sacred and what, when and under what conditions we evolve rituals or create new ones.

- We continue to delve into the tension and complementarity of rituals and practices. We are thinking about practices as things we can adapt and share whereas rituals would need someone from the community to lead.

A lot of these lessons are also captured in the following case study that Laura Webber and John Caulker conducted. Here is what they have to say about it:

This case study came about in the context of an exploration jointly led by Ohio State University and the Corrymeela Community. This exploration began in spring 2020 as a series of virtual dialogue platform between academics and practitioners whose work engages questions and challenges around transitions from violence to peace.

As these conversations unfolded, two pieces became very clear: (1) dominant practices of peacebuilding and reconciliation have not proved effective to bring about sustainable transformation for individuals, communities, or societies; and (2) there is something unique about ritual and ritualized practice that opens a different kind of space of relating, healing, and being together. Ritual holds a powerful potential to foster individual and collective healing and support transitions from violence to peace.

Following this thread, subsequent virtual and in person gatherings were organized to explore how ritual practices were/are supporting reconciliation and individual and social healing across diverse settings of conflict. After the initial virtual platform, the group met in person to look at rituals more broadly. The following year, the group met again to consider transformative practices specifically. The deeply impactful work of Fambul Tok and the prominent role of ritual elements to the Fambul Tok process made it a very compelling case study to craft.1

Fambul Tok: A Case Study of Reintegration, Reconciliation, and Cultural Practices in Sierra Leone

Transitioning from Violence International Consortium

How Rituals, Rites and Ceremonies Can Help with Social Healing, Reintegration and Rehabilitation After Violence

**A PDF version of this case study is also published by the Ohio State University’s Mershon Center.

Introduction

In the years following the end of the civil war in Sierra Leone, many communities most impacted by the conflict continued to suffer greatly from the echoes of violence. Despite government-led efforts of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration, ex-combatants remained largely isolated from and ostracized by their communities. At the same time, communities lacked support to navigate the long journey of reintegration, reconciliation, and social healing in a sustainable way. Fambul Tok (FT) was established as a response to this need for community level healing and reconciliation. The organization aims to center inclusive consultations – going to communities where they live; facilitating explorations of community readiness to reconcile and to welcome back former combatants; and amplifying local resources to navigate these processes. Fambul Tok understands reconciliation and reintegration to be collective and long-term processes that must be community owned and led in order to have sustainable impact.

This inquiry into Fambul Tok focuses on two specific components of its programming as particularly transformative elements, namely community bonfires and cleansing ceremonies. FT adapted these cultural practices from their traditional purpose to the post-civil war context to support community reconciliation, all the while centering community leadership to decide the specific elements involved (such as locally relevant music, dance, and spiritual rituals). Following months of community-led preparation, the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies provide an opportunity for conflict-related harms to be addressed and forgiven, thereby enabling communities to move forward together in the long journey of reconciliation. Together these ritual and ritualized spaces mark a significant threshold in communities’ journeys of reconciliation and reintegration, the components of which this article seeks to explore and elucidate.

This article begins with a background of the civil war in Sierra Leone and post-war transitional justice interventions. Next, important dimensions of Fambul Tok’s organizational history and approach are described as foundational elements to understand the role and process of the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies in the context of community reconciliation and reintegration. This is followed by an analysis of key elements and dynamics of the community bonfires in particular as well as the individual and community level transformations that unfold following communities’ participation in both events. The article concludes with a reflection on challenges and key learnings FT has encountered and integrated over time as the organization continues to adapt and respond to the persistent and emergent social and political challenges facing Sierra Leone.

Context

Sierra Leone’s Civil War

The territory known as Sierra Leone was first settled by tribes originating from the interior of the African continent more than six centuries ago.2 The Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive in the region in the late 1400s, a presence eventually overtaken by the British.3 In 1808, Sierra Leone became an official colony of England.4 In the centuries preceding and during European arrival to the region, archeological and stories passed down in oral traditions suggest a highly conflictual past that pre-dates the onset of the most recent occurrence of civil war, including conflict between indigenous tribes as well as between indigenous tribes and Europeans.5

Sierra Leone gained independence from Britain in 1961. For the subsequent thirty years, the democratic political system became increasingly characterized by corrupt leadership, a centralization of resources, and the abuse of power at all levels of governance. At a national level, political leaders used their offices to concentrate resources in the Sierra Leonean capital, Freetown, as well as to accumulate personal wealth and power. In addition to the democratic political system, the Sierra Leonean social and political landscape is shaped by a chieftaincy system, a legacy of the British colonial administration. Different categories of chiefs that operate at different levels, from the paramount chief that oversees a given chiefdom down to the headman that oversees a given village. The colonial system designed the office of the paramount chief to be very powerful, a position with no term limits and that only members of selected ruling families can hold. In the post-colonial period and pre-civil war period this position of power was often abused to serve chiefs’ personal interests at the particular expense of young men who were left silenced and impoverished.6

In 1991, a group of rebels called the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) invaded Sierra Leone with the proclaimed intent to unseat the incumbent government. The RUF had formed in neighboring Liberia under the leadership of Foday Sankoh and mobilized allegedly in response to the dictatorial rule in Sierra Leone and associated hardships incurred by its citizens. The RUF’s invasion initiated a brutal civil war that extended for eleven years until 2002. The civil war was characterized by extreme violence, particularly wrought by rebel forces. The Sierra Leonean army mounted a response to the RUF, however the lines between the army and RUF became blurred as many soldiers collaborated with the RUF, coming to be known as “sobels” (soldiers turned rebels). In addition to the army and rebel forces, a third fighting force participated in the conflict, namely the Civil Defense Force (CDF), which was composed of community-based civil militias formed to counter rebel aggression.

As the war wore on, the tactics of violence used by rebel forces escalated, including amputations, rape, torture, the burning of villages, and the abduction of children to become child soldiers. Attacks were most frequent in rural areas, where neighbors were often pitted against each other, forced to brutalize or kill one another for fear of being killed themselves.7 The violence forced mass displacement of individuals and communities, some of whom sought safety in local areas while others fled the country entirely to escape the war.

Signed in July 1999 by the RUF and the Sierra Leonean government, the Lomé Peace Accord sought to end the civil war, imposing a ceasefire and providing for a power sharing arrangement between the two parties. The ceasefire was violated several months later, however, reinitiating hostilities that continued until January 2002, when the civil war officially came to an end.

Post-War Transitional Justice and Reconciliation

Following more than a decade of extreme violence that left an estimated 50,000 people dead, hundreds of thousands directly impacted as victims of violence, and 2 million displaced, the need for justice, accountability, and reconciliation was critical. In the immediate aftermath of the war, two primary vehicles were established to meet this need: a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and a Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL).

The establishment of the TRC was provided for in the Lomé Peace Agreement. Predicated on the notion that truth-telling would facilitate individual and collective healing and reconciliation, the TRC, which operated between 2002 and 2004, took thousands of statements from people who incurred and perpetuated violence through written and public testimony. The TRC has been criticized for a number of reasons,8 including for its limited geographic reach as there were few truth commission hearings beyond Freetown. Consequently, Sierra Leoneans living outside the capital in rural communities most impacted by the violence were largely not engaged in the truth commission’s efforts.

The SCSL was jointly established in 2002 by the United Nations and the Sierra Leonean government at the government’s request. The SCSL was notable in its formation as the first hybrid transitional justice tribunal that integrated both domestic and international law. The special court’s mandate extended until 2013, at which point a residual special court was established to manage the court’s ongoing functions. The SCSL’s mandate was to try those who bore the greatest responsibility for the atrocities of the war. Across over a decade of activity, the SCSL indicted 13 individuals, four of whom died before facing prosecution. With a focus on prosecuting high level perpetrators, the special court did not make efforts to engage the general public. Further, it was extremely costly, involving expenditures of hundreds of millions of dollars.

The TRC and the SCSL, while effective in their mandates in certain respects, both suffered significant shortcomings, particularly in their limited cultural relevance and accessibility and thus ineffectiveness to meet the needs of the general population of Sierra Leoneans for healing and reconciliation.

Fambul Tok

Organizational Foundations

Five years after the official end of the civil war, there remained a significant need to support ordinary Sierra Leoneans attempting to navigate daily life, which had been devastated by the violence and its legacies. Fambul Tok, which is Krio for “family talk,” is a national initiative borne out of the recognition of this need and acknowledgement of the importance of centering ordinary citizens’ voices and visions for healing. Centering the belief and practice in Sierra Leone that all Sierra Leoneans are a part of one family, FT sought to answer the question: What went wrong? How could the immense violence of the civil war come to pass in a country where previously people supported and cared for each other as they would members of their own family? To answer these questions, Fambul Tok conducted a consultative process grounded in emergent design8 to listen to and learn from communities about their readiness to reconcile, their vision for how to approach reconciliation, the resources that already exist to support this process, and how FT could provide accompaniment along the way.

From these consultations, it became clear that people were eager to reconcile, to discuss what happened during the war, and to use locally familiar and acceptable practices (namely bonfires, cleansing ceremonies and rituals, and communal feasts) to ground this process. FT drew from this learning to develop a methodology to support communities to organize themselves in the journey of reconciliation. This methodology is grounded in several core values, including:

- Walking with communities to find their own answers: Fambul Tok staff commit to listening to and learning from the wisdom,knowledge, needs, and visions of each community to create an atmosphere where communities can grow into their own potential.

- Meeting people in their communities to listen and learn: FT recognizes the importance of going to people where they live. When people speak from the familiarity of their own village, they feel more secure to share their experiences. Additionally, the presence of other community members impels honesty in the recounting of shared experiences.

- Honesty and respect for all people: Grounded in and emergent from consultative processes,9 Fambul Tok is very intentional about ensuring the voices of all willing community members are heard and represented in decision-making and program implementation. In the early iterations of FT’s programs, it became apparent that particular consideration was required to elevate the voices and ensure the participation of marginalized community members, particularly women and young people. Accordingly, provisions were made through the establishment of mechanisms to facilitate fuller community participation. Elevating the leadership and voice of marginalized community members in these ways served to reassure and encourage greater participation in FT programs.

- Respect for and revival of cultural practices: Fambul Tok centers Sierra Leonean cultural practices and wisdom as the basis of its program. Further, FT recognizes that each village and community has its own approach to and preferences regarding these, including how they might support a reconciliation process. As a community-owned and -led process, each community determines for itself what is needed for reconciliation to unfold. Accordingly, FT programs and activities vary depending upon the local practices and preferences of each community. Among the inevitable diversity of perspectives that exist within a given community, FT encourages the creative embrace of different pathways in the pursuit of healing and reconciliation.

- Total community participation and ownership: FT acknowledges that healing and reconciliation must give every community member the opportunity to engage and all participating community members must feel ownership over the process. The Fambul Tok process is designed to ensure the participation and input of all willing community members and to create the conditions in which communities take on the process as their own. This is done notably through accompanying the creation of community decision-making structures and elevating the leadership of credible community members to coordinate the reconciliation process beginning its earliest phases.

- Restoration of dignity and the right to truth: Fambul Tok recognizes the strength, resilience, and dignity of the communities with whom it works. Through the facilitation and accompaniment of consultative processes in which community members can discuss and make decisions together, its programs and process aim to center the agency and determination of communities to guide their own reconciliation journey. In this process, FT uplifts the importance of truth-telling and public witness as a culturally relevant means through which experiences of the past can be acknowledged and accepted, and reconciliation can be pursued.

Alongside these values and practices, there are two key concepts and understandings that shape and ground Fambul Tok’s work, notably those of creating space and justice. In each component of its programs including consultative meetings, bonfires, cleansing ceremonies, and follow up activities, FT is attentive to the importance of accompanying communities in creating a different kind of space to heal and move forward together. In these spaces, dominant power dynamics and hierarchies are both deliberately and spontaneously transformed such that, for example, women’s voices are elevated, villagers can voice experiences of harm committed by chiefs, and offenders who previously held great power over the offended are rendered vulnerable before the community. Additionally, these spaces embody a collective orientation to and pursuit of justice. Given that the violence of the war affected entire communities, the entire community must be given the opportunity to be involved in the journey of reconciliation, including the significant practice of public apology. It is through collective witness and acknowledgement of harms enacted and incurred that community members can begin to release the burdens of the past and move forward together as one family.

On Process

In the post-civil war period, FT initially worked at a sectional level (clusters of 5-10 villages), beginning with consultations in collaboration with district leaders to identify key stakeholders in each district. Some of these individuals were subsequently recruited as organizational staff. Local staff and district leadership then underwent training in FT values and processes, after which, in consultation and through open ballot voting, they identified communities within their chiefdom who were ready to start the reconciliation journey. Among these communities, FT convened key stakeholders, including community and religious leaders (notably local Imams and Priests), to identify individuals to form two key committees that played crucial roles in the community reconciliation process: a Reconciliation Committee and an Outreach Committee. To ensure committee members were credible and trusted individuals within their communities, certain parameters were put in place to guide their selection. Another important consideration in the selection of committee members was gender parity, to ensure women’s voices were represented in the reconciliation process. Once selected, committee members were trained in the values and process of Fambul Tok, as well in practices of reconciliation, mediation, and community mobilization, before pursuing their respective tasks in the coordination of the community reconciliation process.

The Reconciliation Committee (RC) was responsible for coordinating the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies as well as follow up activities to support and sustain community integration and healing. The composition of RCs was intentionally representative of the range of identities present within a given community, including women, youth, religious, and community leaders, so as to ensure community members would feel their interests were known and protected in the reconciliation process. The Outreach Committee (OC) was responsible for communicating about the FT program to the villages in their respective section. OCs were composed of equal numbers of people who incurred and enacted violence10 the identification of whom was determined through community members’ collective perception of those who were victims and those who were offenders during the war.11

Over the course of three to four months, the OC of a given district would go from village to village to share about the program, identify a date, and collect contributions for the bonfire, cleansing ceremony, and feast. All participating community members are invited to contribute resources to the organization of the events, an important means through which to encourage collective ownership of the process.12 These process elements, it is important to acknowledge, are as important as the events themselves insofar community members work together in their organization and implementation as well as in the coordination of follow up activities. Taken collectively, this provides community members the opportunity to build relationships and engage in collective decision-making over time, the process of which serves to foster reconciliatory relationships and cultivate a culture of peace.

Following months of preparation, communities hosted a bonfire and conducted cleansing or other spiritual ceremonies, which were followed by a communal feast. These sacred spaces were significant in the journey of reconciliation for individuals and communities as a whole, serving as spaces of gathering, truth telling, and spiritual healing, offering unique opportunities for communities to come together in collaborative and mutually supportive endeavors that provided a foundation from which reconciliation could grow.

Sustaining Transformation

In the recognition that reconciliation is a process not an event, a number of activities followed the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies to accompany and support long-term community healing. These activities are determined and organized by each community such that the specific activities and the way in which they are pursued across regions and districts vary. Importantly, RC and OC members continued to be involved, providing leadership and accompaniment in their community’s reconciliation journey. Follow up activities have included:

- Peace Mothers: The Peace Mothers program features as a central and transformative initiative of Fambul Tok. It emerged in recognition of the ways in which women suffered during the war as victims of sexual and physical violence, as well as the unique ways in which they continued to suffer in the post-war period. Through consultations in various regions, women voiced a desire for FT to support them to hold a space to simply be together and support one another. In these gatherings, the women would not only offer one another emotional support, but also create initiatives to support and sustain peace in their communities, for example through economic development, social entrepreneurship, child education, and public health interventions.

- Community Farms: Some villages and communities chose to create community farms in which people who incurred and enacted violence to work side by side, together preparing the land, planting, and harvesting crops. Following the harvest, community members decide together how the crops will be used. These farms provide an opportunity for people to work together toward a common goal over an extended period of time, a powerful means through which to cultivate a different kind of relationship, one not only defined by the experience of harm, but also by interdependence.

- Peace Tree: A dedicated tree in a given village that provides a space for follow up conversation to discuss unresolved tensions that arose during the bonfire as well as for the mediation of conflicts (both those related to the civil war and newly emerged relational and community conflicts). Trained in mediation and community healing, RC members serve as mediators of these conversations, facilitating a peaceful navigation of the inevitable obstacles that arise in reconciliation.13

- Football for Reconciliation: Communities in a given section organize a day of short football matches in which each member of the community has the opportunity to participate. The matches are accompanied by music, wherein songs are played that encourage peace. Following the football matches, a disco is held whereby people dance all night before returning home in the morning. Through sport, play, music, and dance, communities can strengthen positive relational bonds, thereby promoting the development of social cohesion and deepening of healing.

These programs enable a deepening of the healing and forgiveness the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies serve to initiate, thereby contributing to the development of a culture of peace in Sierra Leone. Fundamental to this process is the centering of resources that exist within Sierra Leonean tradition and culture, uplifting communities-held wisdom about and leadership in the pursuit of reconciliation.

Adapting Cultural Practices for Social Healing

Bonfires, rituals, and cleansing ceremonies hold deep culture, relational, and spiritual significance in Sierra Leone. Before the civil war, it was common in villages for young people to organize bonfires around which the whole community would gather. These bonfires provided spaces for community storytelling, where young people could ask questions of their elders, and elders could share folklore and stories about the past. Cleansing ceremonies and rituals were traditionally conducted annually or on specific occasions, serving as vehicles through which to commune with the ancestors, for example to seek protection or bless the year’s harvest. Due to the violence and subsequent displacement caused by the civil war, bonfires and rituals were not practiced during the war or in the immediate post-war period, however they persisted in the lived and cultural memory of communities as resources people were keen to draw upon to support community reconciliation.

Bonfires

In the Fambul Tok process, bonfires take place on a date determined through consultation and are resourced through the collective contributions of the communities involved. They open with statements from community or religious leaders who set the tone of the space, framing it as a forum in which to have frank discussions about the past and move forward collectively. They encourage people to feel free to say whatever is disturbing their heart and mind, providing assurance that whatever someone shares would not be used against them. In declaring the space open, they evoked the presence of the spirits of God and the ancestors to touch the hearts of the offended and those who offend. With this framing, the floor is opened for people to spontaneously come forward to share their experience of harm and to ask for or extend forgiveness. The bonfires would last as long as necessary for everyone who desires to come forward to speak, sometimes extending a few hours and sometimes enduring all the way through the night.

The bonfires provided the opportunity for community members to share their experience during the war, whether as someone who enacted or incurred violence (experiences that were rarely mutually exclusive as many people who enacted violence were themselves victims of the conflict as well).

This is an act that takes tremendous courage, as many people shared experiences they had kept hidden, unable to voice to their community since the war. Once they shared their experience of wounding, people were able to extend and request apology, as well as request and receive forgiveness.

The bonfires were simultaneously a solemn and celebratory space. For many communities, the bonfires were the first time to come together since the war, which in itself was something to celebrate. This celebratory dynamic was embodied through singing, dancing, and drumming. Different kinds of songs animated the bonfires – some with religious undertones, some deeply traditional, and others newly composed for the occasion. The specific songs and dances performed were determined by the community and their respective traditions and thus differ for each bonfire. They often took place as an interlude between testimonies, providing time and space for people to choose to come forward before their community.

At the same time as it was an occasion to celebrate, people would also share experiences of deep distress and harm. These shares would sometimes be met by heavy silence and at times awaken latent tensions. For example, on one occasion, an individual shared about a murder he had committed, killing a beloved member of the community. The family of the deceased had been in denial, believing that their loved one was living in Liberia. Upon learning of the death of this community member, a profound depth of the grief was awakened for the family, so much so that the bonfire had to be stopped. On another occasion, a man confessed before the community that he had burned the village’s court barrie (town hall in Krio). The community initially rejected his request for forgiveness, instead desiring revenge and began to physically rush at the man. The Reconciliation Committee had to intervene to deescalate the situation and mediate the space.

Cleansing Ceremonies

The next day following the bonfires, community members participated in cleansing ceremonies which consist of rituals to awaken, commune with, and appease the ancestors. These ceremonies are important as a means through which to connect to the ancestors, and thereby connect to God. The specific rituals involved in these ceremonies vary significantly from village to village, from region to region. They may include the pouring of libations in a sacred site in or close to a village, partaking in prayers at the village church and/or mosque, or performing sacrifices of chickens or sheep. In some communities, the cleansing ceremonies integrated a range of different practices, including those that are more cultural, such as the pouring of libations or performing sacrifices, as well as those that are more traditionally religious, such as praying at the church and/or mosque. This is one way among others in which the diversity of community members’ perspectives and preferences regarding the pursuit of reconciliation was honored and integrated into the reconciliation process.

The cleansings ceremonies play a vital role in the wellbeing of the community. For example, during the war, many acts of extreme violence, including murder and rape, happened in the fields and the bush surrounding villages. In the years following the war, many communities experienced poor harvests, which was commonly understood to be caused by the ancestors’ anger about the violence that took place. After performing ceremonies to appease the spirits of the ancestors, communities were graced by a bumper harvest, which community members believe to have been as a result of these rituals. To the extent that there was greater collective involvement in community farming following the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies, it is also possible that greater collaboration and participation among community members contributed to improved harvests.

On Bonfires and Reconciliation

In the Fambul Tok process, the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies serve as transformative collective spaces that mark a turning point in communities’ long journey of reconciliation that continue to feature in FT’s work into the present. Following these events, the community committed to begin anew, moving on collectively as one family. The labels of victim and offender often fell away as people agreed to see and be with one another as fellow family and community members. Alongside the acknowledgement that community reconciliation is a long-term commitment, there are aspects of the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies that served as powerful elements to both initiate and sustain this commitment. This section will explore several of these elements, with a primary focus on the bonfire space as they are most consistent across the districts in which FT works, in contrast to the cleansing ceremonies, which vary much more significantly from district to district, chiefdom to chiefdom, and village to village.

Public Apology

The bonfire spaces draw up on the cultural significance of public apology and practice of forgiveness in Sierra Leone, both of which connect deeply into perceptions of justice for individuals and communities. In Sierra Leone, when a public apology is extended whereby the whole truth is shared with a demonstration of remorse, people who incurred violence are nearly bound to accept, thereby entering into an agreement with the person who offended them to commit together to the journey of reconciliation.

The collective understanding of identity in Sierra Leone makes it such that a harm imposed on an individual is a harm to their family and their community. It is vital that an apology is requested and granted before the community such that everyone is witness to the exchange, thereby enabling the community to move forward together. Further, when an accusation of harm is leveled against an individual or if an individual has been harmed, their entire family likewise bears the burden. Accordingly, if an offender is not present at a bonfire, a member of their family can come forward to apologize on their behalf. Similarly, if someone who incurred an offense is not present, a member of their family can accept an apology on their behalf.

Thus, the bonfires play a vital role in community reconciliation by providing a space for people to share their experiences and receive or extend apology before the community. Through public apology, people who incurred and enacted violence, with community witness and accompaniment, are supported to move forward together. Further, the community presence enables all those impacted by the harms described to receive or extend forgiveness, thus engaging the whole community in the healing journey.

Transforming Identity

Although in Sierra Leone there is often a cultural obligation to accept public apology, it is also a source of empowerment and justice for people who incurred violence during the conflict. During and after the war, those who enacted violence wielded great power over offended individuals and communities. As they come forward to ask for forgiveness, they are rendered vulnerable before their community. In this shifting of roles, people who incurred violence reclaim their agency through choosing to forgive (or not) and voicing what they require to extend forgiveness. In this way, people who have been harmed are given the opportunity to transform their self-perception from one of victimhood to one characterized by agency and strength. Further, when those who offended share their experiences during the conflict with an expression of remorse, community members’ perceptions of them often shift, as they come to see how they too suffered as victims of the conflict. In this way, the bonfires support people who incurred and enacted violence as well as the community as a whole to transform individual and collective identities and narratives of the past in service of justice, healing, and peace.

Suspending Hierarchies

The bonfires offer unique spaces in Sierra Leone in which both traditional and conflict-generated power dynamics and social hierarchies dissolve. For example, there have been instances where community members have accused village and paramount chiefs of wrongdoing, to which the chiefs have confessed and apologized. In a culture where chiefs traditionally hold great power, there are few if any other spaces that exist where a chief’s power could be challenged in this way without resulting in the accusing individual being banned from the community.14 In such circumstances, the presence and support of the community is very important, as community members will support and encourage people who incurred harm to share their story, giving them the courage and confidence to do so.

The sharing of testimonies at the bonfires is done spontaneously such that no one knows who will come forward to share their story, and thus who will be asked to apologize or extend forgiveness. In this way, the subverting of social hierarchies is unplanned. It is notable, however, that Fambul Tok as an organization is very attentive to the impact of cultural and social power dynamics as they may impact or impede community reconciliation. FT works actively with communities to explore ways in which their programs can be as inclusive as possible. It was often the chiefs who demonstrated the greatest resistance to the inclusion of marginalized community members as they see themselves as the custodians of traditional practices, which overwhelmingly favor adult men. To navigate this resistance, FT leadership would meet directly with local, district, or paramount chiefs, explaining the importance of including especially women and young people into reconciliation processes. In these conversations, the framing and approach is critical so as to emphasize the necessity of an inclusive approach to reconciliation and at the same time ensure chiefs do not feel their authority in the community is threatened.

For example, certain rituals are traditionally performed by either men or women to enable communion with male and female ancestors, respectively. In some cases, women have been excluded from ceremonies traditionally conducted by men and denied the opportunity to commune directly with their ancestors. In acknowledgement of the unique and acute suffering women experienced during the war, FT encourages the adaptation of traditionally male-dominant or male-only rituals to create more space for women’s involvement. In one highly traditional village, male community leaders resisted the presence of women at a given shrine at which libations are poured to the ancestors. Through facilitated discussion, a compromise was reached whereby the women could join the men for part of the procession toward the shrine, then stop at a proximate place to allow the men to continue to the shrine for the pouring of libations. This solution was satisfactory for men and women in the village and constituted a shift of a previously closed traditional practice toward greater inclusiveness. In such ways, Fambul Tok’s accompaniment of the ceremonial process has served to encourage communities to adopt the peace-promoting values and practices of inclusion, dignity, and healing.

Process, Ownership, and Trust

The bonfire is a powerful space of truth telling, where people come forward to share vulnerably and openly about the harms they committed or incurred. The transformative quality of the space can be traced to both the mystical dimensions of the fire as well as very practical aspects of the process by which the bonfires are organized. In some ways, there is a quality of space the fire creates that remains mysterious, eliciting intangible and spiritual dimensions of being that give people the courage to come forward.15 At the same time, community members have deep trust in the space, resulting from their sense of ownership over its emergence, the presence of trusted leaders holding key roles in its organization and facilitation, and their confidence in Fambul Tok as an organization to accompany their community in their process of reconciliation. This trust contributes to community members’ confidence to come forward and confess or express their experience of harm.

Ritual Transformations

The bonfires and cleansing ceremonies are embedded in a long-term, collective process of reintegration and reconciliation and serve as a pivotal collective and ritualized experience from which communities can move forward together. There are numerous observable shifts that unfold following these events at both the individual and communal levels. While some of these shifts can be attributed to the bonfire and cleansing ceremony experiences, it is also important to acknowledge the broader process in which these events are situated. Whereas certain transformations have been observed following the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies, they unfold from a foundation of intentional community engagement, which contributes significantly to the effectiveness of these ritualized spaces in communities’ collective journey of reconciliation. With this acknowledgement, this section will focus on transformations observed specifically emergent from these events in their contribution to the long-term journeys of reconciliation and reintegration.

Agency, Dignity, and Engagement

At an individual level, following participation in the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies, it is common for people who incurred and enacted violence to demonstrate marked shifts in how they move and act in their communities. Prior to these experiences, certain individuals would walk slowly, displaying a sense of weariness and isolation. Weighted by the burden of shame and silence, people who incurred or enacted violence tended to isolate themselves – a detachment, particularly for ex-combatants, that was reinforced by the community who did little to welcome these individuals back. After the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies – after people have the opportunity to voice their burden, be witnessed by their community, and extend and receive forgiveness – the demeanor of many individuals transforms as they move with greater confidence and engage more actively in community activities. This is particularly notable for some ex-combatants who demonstrate a great eagerness in their engagement in community projects and structures that is often significantly motivated by a desire to display remorse and offer repair for harms committed during the conflict.

Community Cohesion

Following the war, community life in many villages was characterized by siloing as people would keep to themselves, disengaged from one another and community life. To address this, the FT process intentionally creates opportunities for all community members to participate from the very beginning, accompanying their determination of when and how they approach reintegration and reconciliation. All willing community members are engaged in the planning and preparation of the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies and are invited to participate to the extent they feel comfortable to do so. Whereas community members begin to come together in the preparation for these events, the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies mark a significant transition point after which a renewed sense of community cohesion emerges, demonstrated in a variety of ways.

Following these events, people begin to come together to work together, to discuss community matters, and engage in development initiatives. People who incurred and enacted violence as well as other community members work together on community farms, micro-lending collaboratives, and supporting access to healthcare and education, particularly for less privileged individuals. Whereas numerous communities suffered from poor harvests following the war, many experienced bumper harvests in subsequent years following the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies. As a further example, one community located a great distance from a medical facility gathered contributions from community members to purchase a motorbike to transport pregnant women in labor to the nearest hospital, an initiative that has saved the lives of many women and children. Such an initiative would not have been possible without community members joining and working together, a collaboration made possible through the relational repair initiated by the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies.

In addition to contributing to community development initiatives, many community members display an increased engagement with collective decision-making processes. Through Fambul Tok programming, new structures are put in place to involve entire communities in decisions that affect them. In a shift from the traditional dynamic whereby chiefs dictated such decisions, following the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies, community members become emboldened to hold chiefs to account, ensuring decisions are made that are just and equitable for all community members, not only in the interest of the chief. Further, the establishment of these structures contributes to the sustainability of community reconciliation and healing beyond FT’s direct involvement by embedding mechanisms for collective decision-making (and conflict mediation) into the very fabric of community governance and life.

A third notable shift reflecting greater community cohesion following participation in the FT process generally, and the bonfire and cleansing ceremonies specifically, is an increase in community visibility and pride. Many communities were nearly extinguished because of the war as people left their homes in search of a better life in bigger towns. As communities began to organize reconciliation processes, places previously known as sites of atrocity during the war came to be seen as places of healing and reconciliation. Alongside this shift in how communities were perceived, the inclusive process and approach to the process gave people confidence to return. In some cases, returnees were people who returned to their communities of origin, while in others, it was ex-combatants who returned to the communities in which they were responsible for committing harm. While some people returned simply to observe only a given bonfire event and cleansing ceremony, others took the opportunity to participate in the events and/or subsequent follow up activities. In such ways, the events contributed to the restoration of community life previously decimated by the war.

A final significant transformation that unfolds for communities through their participation in the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies is in the way in which conflict is navigated. During and following the war, community members would navigate conflicts either through violence or bottling up their suffering, carrying the weight of it on their own. When initially consulted regarding their willingness and readiness to reconcile, many communities not only expressed great eagerness, they voiced a desire to do so through cultural practices that were subsequently adapted to the contemporary context and needs, namely to navigate community conflict and accompany the process of reconciliation. The reinvigoration of these cultural practices, alongside the creation of Reconciliation Committees and the establishment of Peace Trees, collectively contributes to a cultural shift toward nonviolence in which conflicts and community issues are resolved through dialogue rather than violence.

When initially consulted, many communities expressed an eagerness to reconcile, however in other instances, communities were not ready to engage in the journey of reconciliation or were skeptical of NGO (non-governmental organization) activities, particularly following the saturation of external interventions that took place in Sierra Leone in the post-war period. In these circumstances, Fambul Tok would respect the community’s decision, pursuing programs in neighboring regions. It was often the case that after communities witnessed the effectiveness of FT programs over time, chiefs or other community leaders would reapproach the organization, requesting its presence and support to pursue reconciliation.

Challenges

In creating and conducting the bonfires and cleansing ceremonies, there were numerous challenges encountered resulting from Sierra Leone’s post-war and cultural context, the navigation of which were vital to and formative of the success of Fambul Tok programs. Two of these challenges directly related to the bonfire events pertained to ensuring the safety of ex-combatants if and as they shared their war-time experiences. A third notable and multifaceted challenge arose in relation to the political landscape during and following the civil war.

When ex-combatants came forward to confess their harms and request forgiveness, in many instances the harms described were already known to community members. However, there were numerous instances in which people shared knowledge or confessed harms that were as yet unknown. Such testimonies were particularly emotional for communities, and on one occasion led to community members rushing at an ex-combatant in anger and vengeance. The community’s emotions overwhelmed the cultural practice of public apology, demonstrating the visceral nature of the hurt and anger community members carried after the war. To ensure the safety of all community members, particularly those sharing testimony at the bonfires, provisions were made through the presence of the Reconciliation Committee and additional community leaders to intervene as needed to protect the individual at risk and de-escalate the conflict. Although the bonfire spaces hold a sacred quality, they are not immune from conflict – a human reality and inevitability in the journey of reconciliation and reintegration that must be accepted and navigated with care.

A second challenge related to the post-war context that influenced participation in bonfires was the existence of other post-conflict structures, particularly the Special Court. High profile perpetrators or offenders who were in close proximity to these individuals during the war feared confessing at the bonfires, wary that their testimonies would lead to their being indicted and prosecuted at the Special Court. These cases required careful navigation, at times necessitating bonfires be delayed until individuals were no longer at risk of prosecution. This experience illuminates the complex interplay of initiatives and dynamics that characterize post-war contexts. In accompanying the development of ritual and transformative processes to support reconciliation and reintegration after violence, it is critical to acknowledge and account for the ways in which initiatives may influence one another, or even run at cross purposes.

In order to work at the chiefdom, section, and village levels, it was necessary for Fambul Tok to first communicate with and obtain permission from the chiefs, especially the paramount chief. When initially approached, chiefs were largely open to the development of FT programming, however some would seek to manipulate the process, for example by elevating members of their family into leadership positions in the FT process, notably as members of the Reconciliation Committee. In response, FT implemented a spot check system that verified the credibility and neutrality of nominated community members and thereby circumvent possibilities for nepotism. Further, whereas in initial iterations FT intentionally involved paramount chiefs directly into its programs, it became evident that the power dynamics this engaged inhibited the potential for deep community leadership. FT subsequently adjusted its approach, establishing a structure in which community leaders would report to the paramount chief without the chief engaging directly. This facilitated greater community ownership over the process and at the same time respected the authority of the paramount chief, which was critical to enable the program to continue with the chief’s blessing. The political landscape during and following Sierra Leone’s civil war was highly contested with leaders representing different parties dominating in different regions. As an organization with a mission to accompany reconciliation, it is important for the integrity of the organization to remain politically neutral. This awareness guided FT’s selection of regions in which to work, namely choosing regions that are politically divided. By avoiding regions dominated by particular political parties, the organization could avoid any perception that it is aligned with or supportive of a given leader or party.16 Further, as the organization became popular and gained elevated regard in national awareness, political leaders would often ask to attend community consultations or events with the intention to benefit from their association with the organization. In these cases, FT leadership would intervene, carefully communicating to the politicians in question that the community gatherings and events were for community members only so as to protect the organization and programs from political interference.

Conclusion

The Fambul Tok process centers community ownership through inclusive consultations and a commitment to accompany communities in their own collectively determined journey toward reconciliation and reintegration. This approach is built on the belief that true peace only be achieved when it is grounded in and owned by communities and informed by the collective voice of all community members. Further, the Fambul Tok experience illuminates that reintegration and reconciliation are collective and long-term journeys that include preparatory work, culturally grounded practices to facilitate relational repair, and ongoing opportunities to affirm and sustain the commitment to reconciliation.

As the social, political, and cultural landscape evolves in Sierra Leone, Fambul Tok’s programs and structures that were initially designed for the post-war context are being adapted to meet contemporary needs. Significantly, FT programs were effectively adapted to support communities to navigate the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone in 2014, which placed immense strain on community cohesion and welfare. As Sierra Leone’s context continues to evolve, FT is providing support at the village level to coordinate bonfires, cleansing ceremonies, and establish community mediation structures to support the navigation of local conflicts and sustain reconciliation. Prior to Fambul Tok’s accompaniment, community members would turn to their chiefs or the court system to navigate conflicts, which would often entail a significant financial cost for individuals and families. With the implementation of community reconciliation structures such as the Peace Tree, Reconciliation Committee, and bonfire events and cleansing ceremonies, community members now more frequently turn to these mechanisms to address and transform the conflicts they face. While not all conflicts and cases are able to be addressed through these means (for example certain land rights cases or rape cases), the existence, desire for, and use of these structures in Sierra Leone’s contemporary context demonstrates not only their value for communities, but also a cultural shift in how conflict is navigated at a community level, namely with greater individual and community agency and commitment to reconciliation.

In the journey to build sustainable peace in Sierra Leone, the ritual and ritualized components of the Fambul Tok process are potent experiences for violence-impacted communities. They reconnect communities to customary practices lost through the war, create a space in which communities come together and collectively affirm a commitment to repair and reconcile, provide an opportunity for public apology and forgiveness, and enable communion with the ancestors, thereby facilitating repair in the spiritual realm. Situated in an extended process of reconciliation and reintegration grounded in community engagement and accompaniment, these experiences are particularly pivotal for ex-combatants to be welcomed back into their communities and for communities as a whole to move forward together as one family, wan fambul.

Bibliography

“About Sierra Leone: History.” United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone. n.d. https://unipsil.unmissions.org/about-sierra-leone-history.

Albrecht, Peter, and Paul Jackson. “Non-Linearity and Transitions in Sierra Leone’s Security and Justice Programming.” International Peacekeeping 28, no. 5 (August 27, 2020): 813–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2020.1812393.

Anderson, Samuel Mark. “Times Past Under Fire: Accounting for the Efficacy of Reconciliation Rituals in Postwar Sierra Leone.” Essay. In The Art of Emergency: Aesthetics and Aid in African Crises, edited by Chérie Rivers Ndaliko and Samuel Mark Anderson, 249–79. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Basu, Paul. “Confronting the Past?” Journal of Material Culture, July 1, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183508090896.

Cilliers, Jacobus, Oeindrila Dube, and Bilal Siddiqi. “Reconciling after Civil Conflict Increases Social Capital but Decreases Individual Well-Being.” Science 352, no. 6287 (May 13, 2016): 787–94. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9682.

Cole, Courtney E. Ms. All in the “Fambul”: A Case Study of Local/Global Approaches to Peacebuilding and Transitional Justice in Sierra Leone. Waltham, MA, 2012.

Dupuis, Pauline. “Peacebuilding and Transitional Justice in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Post-Conflict Societies: The Role of Traditional Forms of Justice in Post-Civil War Sierra Leone.,” 2018.

Grawert, Elke. Ms. Between Reconciliation, Resignation and Revenge: (Re-)Integration of Refugees, Internally Displaced People and Ex-Combatants in Sierra Leone in a Long-Term Perspective. Bonn, 2019.

Graybill, Lyn S. “Traditional Practices and Reconciliation in Sierra Leone: The Effectiveness of Fambul Tok.” Conflict Trends, no. 3 (2010): 41–47.

Higgins, Sean. “Culturally Responsive Peacebuilding Pedagogy: A Case Study of Fambul Tok Peace Clubs in Conflict-Affected Sierra Leone.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 28, no. 2 (2019): 127–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620214.2019.1580602.

Hoffman , Elizabeth (Libby). “Reconciliation in Sierra Leone: Local Processes Yield Global Lessons.” The Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 32, no. 2 (2008): 129–41.

Iliff, Andrew R. “Root and Branch: Discourses of ‘Tradition’ in Grassroots Transitional Justice.” International Journal of Transitional Justice 6, no. 2 (March 26, 2012): 253–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijtj/ijs001.

Jackson, Paul. “Chiefs, Money and Politicians: Rebuilding Local Government in Post-War Sierra Leone.” Public Administration and Development 25, no. 1 (2005): 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.347.

Jones, Alex. “What Was Sierra Leone like before British Colonisation? 1500–1800.” Medium, April 27, 2022. https://alex-jones.medium.com/britains-colonisation-of-sierra-leone-the-creation-of-inequality-daccabb58751.

Kelsall, Tim. “Truth, Lies, Ritual: Preliminary Reflections on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Sierra Leone.” Human Rights Quarterly 27, no. 2 (2005): 361–91. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2005.0020.

Kovac, Uros. “The Savage Bonfire: Practising Community Reconciliation in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone,” 2012.

Mac Ginty, Roger. “Indigenous Peace-Making Versus the Liberal Peace.” Cooperation and Conflict 43, no. 2 (2008): 139–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836708089080.

Martin, Laura S. “(En)Gendering Post-Conflict Agency: Women’s Experiences of the ‘Local’ in Sierra Leone.” Cooperation and Conflict 56, no. 4 (2021): 454–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/00108367211000798.

Martin, Laura S. “Deconstructing the Local in Peacebuilding Practice: Representations and Realities of Fambul Tok in Sierra Leone.” Third World Quarterly 42, no. 2 (2020): 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1825071.

Martin, Laura S. “Practicing Normality: An Examination of Unrecognizable Transitional Justice Mechanisms in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 10, no. 3 (2016): 400–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1199480.

Millar, Gearoid. “Between Western Theory and Local Practice: Cultural Impediments to Truth-Telling in Sierra Leone.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2011): 177–99. https://doi.org/10.1002/crq.20041.

Moore, Jina. Rep. Edited by Libby Hoffman. Fambul Tok International: Community Healing in Sierra Leone and The World. Freetown, Sierra Leone: Fambul Tok International, 2010.

Park, Augustine S.J. “Community‐based Restorative Transitional Justice in Sierra Leone.” Contemporary Justice Review 13, no. 1 (2010): 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10282580903343134.

Raghu, Pratik. “From Retribution to Restoration in Sierra Leone: Fambul Tok’s Drive to Heal Post-Civil Communities.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse 7, no. 7 (2015).

Stark, Lindsay. “Cleansing the Wounds of War: An Examination of Traditional Healing, Psychosocial Health and Reintegration in Sierra Leone.” Intervention 4, no. 3 (2006): 206–18. https://doi.org/10.1097/wtf.0b013e328011a7d2.

Stepakoff, Shanee, Jon Hubbard, Maki Katoh, Erika Falk, Jean-Baptiste Mikulu, Potiphar Nkhoma, and Yuvenalis Omagwa. “Trauma Healing in Refugee Camps in Guinea: A Psychosocial Program for Liberian and Sierra Leonean Survivors of Torture and War.” American Psychologist 61, no. 8 (2006): 921–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.61.8.921.

Stovel, Laura. “‘There’s No Bad Bush to Throw Away a Bad Child’: ‘Tradition’-Inspired Reintegration in Post-War Sierra Leone.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 46, no. 2 (2008): 305–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022278x08003248.

Taylor, Louise. Rep. “We’ll Kill You If You Cry”: Sexual Violence in the Sierra Leone Conflict. Vol. 15, no. 1(A). New York, NY: Human Rights Watch, 2003.

Taylor-Smith Larsen, Rodmire. “Coping as an Ex-Combatant: Strategies of Interaction and Re-Integration,” 2011.

United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone. “About Sierra Leone: History.” n.d. https://unipsil.unmissions.org/about-sierra-leone-history.

Werkman, Katerina. “Understanding Conflict Resolution Community Reconciliation through Traditional Ceremonies.” Central European Journal of International and Security Studies 8, no. 2 (January 2014): 115–36.

*This case study was made possible with the support of Ohio State University’s Mershon Center.

- This case study was made possible with the support of Ohio State University’s Mershon Center. This case study is also co-published as a PDF here ↩︎

- United Nations Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Sierra Leone, “About Sierra Leone: History,” n.d. https://unipsil.unmissions.org/about-sierra-leone-history. ↩︎

- Jones, Alex, “What Was Sierra Leone like before British Colonisation? 1500–1800,” Medium, April 27, 2022, https://alex-jones.medium.com/britains-colonisation-of-sierra-leone-the-creation-of-inequality-daccabb58751. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Paul Basu, “Confronting the Past?,” Journal of Material Culture, July 1, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183508090896. ↩︎

- Paul Jackson, “Chiefs, Money and Politicians: Rebuilding Local Government in Post-War Sierra Leone,” Public Administration and Development 25, no. 1 (2005): 49–58, https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.347. ↩︎

- Laura Stovel, “‘There’s No Bad Bush to Throw Away a Bad Child’: ‘Tradition’-Inspired Reintegration in Post-War Sierra Leone,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 46, no. 2 (2008): 305–24, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022278x08003248. ↩︎

- Kelsall, Tim, “Truth, Lies, Ritual: Preliminary Reflections on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Sierra Leone,” Human Rights Quarterly 27, no. 2 (2005): 361–91, https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2005.0020. ↩︎

- For more information on Fambul Tok’s approach to consultation, please see: https://www.fambultok.org/programs/peoples-planning. ↩︎

- Throughout this text, references will be made to people who incurred and enacted violence during the Sierra Leonean civil war. In using this terminology, the authors hold an awareness that these categories, often termed ‘victim’ and ‘offender,’ are neither binary nor fixed, and that many people who enacted violence as combatants during the war were also subjected to extreme violence themselves in the form of direct physical violence or coercion. ↩︎

- In communities’ perception of victims and offenders, victims were those who did not participate in the violence, who ran away, or resisted the arrival of armed groups to their village. Offenders were those who participated in the war as active combatants, who enacted violence and often who led armed groups to villages that were subsequently attacked ↩︎

- In the case that communities lack the adequate resources to conduct the events, Fambul Tok can provide additional resources. For example, there have been instances where a community’s customary practice is to sacrifice a lamb, however it lacks the resources to purchase a lamb. In these cases, Fambul Tok will either purchase the lamb on the community’s behalf or discuss creative solutions with community leaders, such as performing the sacrifice with a chicken instead of a lamb ↩︎

- For example, following the bonfire and cleansing ceremony in one community, a former combatant went to visit the person he had harmed wearing the same color shirt he had worn when he committed the offense. Though the former combatant intended the visit to be amical, the person who previously incurred violence interpreted his choice of clothing as an incitement into further conflict. These individuals were able to bring their conflict to the Reconciliation Committee, whose members were able to facilitate mutual understanding between the two men. ↩︎

- In Sierra Leone, the relative power and position of chiefs varies across localities. This may have contributed to the variation of community members’ engagement with and confidence to speak of their experiences of harm incurred at the hands of local chiefs. ↩︎

- This observation emerges from the direct experience of co-author John Caulker through his participation in and accompaniment of dozens of community bonfires. ↩︎

- Initially, Fambul Tok worked in two districts in each of the three regions chosen for programming. However, with a desire to engage with communities in greater depth, a decision was made to focus on communities in one district per region. ↩︎